They’re hard to spell and even harder to pronounce, but these ulcer-causing bacteria infect nearly half the world’s population. And if you have them, you’re also at increased risk for gastric cancer.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) bacterial infections are less common in advanced countries, such as the United States, than in the developing world, as is gastric cancer—cancer of the stomach or the gastroesophageal junction, where the esophagus meets the stomach. Still, H. pylori infection is the strongest known risk factor for gastric cancer, the 15th most common cancer in the United States and the world’s second deadliest cancer.

While H. pylori infections are on the decline in the United States, it makes sense to pay attention to your gut for potential symptoms, especially if you fall into one of the higher-risk groups for stomach cancer, says Pankaj Vashi, MD, Head of the Gastroenterology and Nutrition Department at Cancer Treatment Centers of America® (CTCA).

This article will explore:

- What are H. pylori?

- Who gets H. pylori?

- What is H. pylori’s connection to cancer?

- Who should be tested and treated for H. pylori?

If you’ve been diagnosed with cancer of the digestive system and want to learn more about treatment options at CTCA®, or you’re interested in a second opinion on your cancer diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.

What are H. pylori?

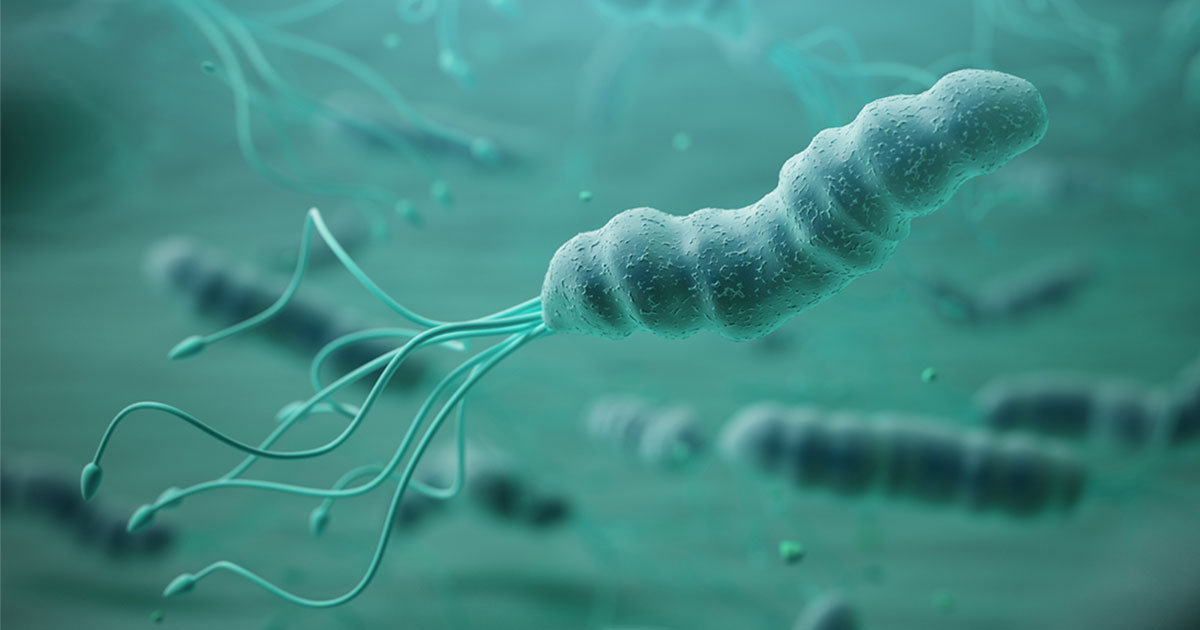

H. pylori are bacteria that infect the stomach and upper small intestine. They may cause redness or inflammation of the stomach lining and are the most common cause of peptic ulcers.

H. pylori burrow into the stomach lining, where they proliferate. The bacteria are shielded from the harsh stomach environment by urease, an enzyme they secrete that produces ammonia, which neutralizes stomach acids. They also have multiple mechanisms that allow them to evade bacterial attacks launched by immune system cells.

Who gets H. pylori?

Research conducted in 2017 found that infection rates were as high as 87.7 percent in Nigeria and as low as 18.9 percent in Switzerland. Studies estimate the infection rate at 30 to 40 percent in the United States, with higher percentages in Asian and Hispanic populations.

Developing nations are often a breeding ground for the bacteria because of a number of issues, including contaminated water and high-density populations. People with many siblings and extended families who live together or in close proximity are at greater risk of being infected—and reinfected.

“There is a direct relationship between the number of households living under one roof and the prevalence of H. pylori. In the United States, it is more common among those who tend to live in a joint family, with more people under one roof,” Dr. Vashi says. “If one person is treated for H. pylori, it is likely they will get it again if other members of the family also have it. It’s a transmittable condition that you can get from others.”

Research shows H. pylori is generally spread at an early age, commonly from mouth-to-mouth transmission or from mother to child, but its symptoms may not surface until decades later.

What is H. pylori’s connection to cancer?

H. pylori bacterial infections have been linked to two types of stomach cancer:

- Non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma, the most common stomach cancer, which affects the lower portions of the stomach

- Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, a very slow-growing, rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that develops outside the lymph nodes

“There is definitely a very good relationship between H. pylori and chronic gastritis and stomach cancer,” Dr. Vashi says. Some researchers have speculated that H. pylori’s ability to create a long-term inflammatory response may make cells in the stomach lining more predisposed to becoming cancerous, according to the National Cancer Institute.

The connection is particularly remarkable with MALT lymphoma. “If patients have MALT lymphoma and also H. pylori bacteria on the biopsy, if you treat the H. pylori, many MALT lymphoma have very positive outcomes—that’s how strong the association is with those two,” Dr. Vashi says.

Researchers are continuing to investigate the different strains of H. pylori to determine the bacteria’s connection to gastric cancer. But so far, while gastric cancers have declined in some countries that have seen rates of H. pylori infection drop, a clear line has not yet been established between the two.

“We have seen the H. pylori prevalence go down significantly, but the gastric cancer incidences have not gone down at the same ratio, so we know there are other factors that are causing stomach cancer,” Dr. Vashi says.

Gastric cancer is more common in seniors, men and in people who eat significant amounts of salted, smoked or poorly preserved foods. Other risk factors include:

- Tobacco use

- A diet low in vegetables or fruits

- Pernicious anemia, a condition in which the blood cells cannot absorb vitamin B-12

- A family history of gastric cancer

- Previous stomach surgery

Who should be tested and treated for H. pylori?

Most people infected with these bacteria don’t experience symptoms. When an infection causes an ulcer, gastritis or other stomach distress, doctors typically prescribe antibiotics in combination with an acid blocker to kill the bacteria. The prescribed antibiotic regimen can be harsh on patients—most of whom aren’t experiencing symptoms in the first place.

“The theory used to be that we should check everybody for H. pylori, even if they don’t have symptoms,” Dr. Vashi says. “The idea of eradicating everybody’s bacteria is really not logical. That treatment is pretty aggressive. It’s not well tolerated by everybody.” There’s also a growing concern that widespread treatment would increase the chances of H. pylori developing even greater antibiotic resistance.

Dr. Vashi says people who are experiencing stomach symptoms that may be connected to H. pylori—“and it could be any vague symptoms: upset stomach after eating, cramping”—should undergo a simple blood test to identify whether H. pylori antibodies are present.

“If the test is positive for H. pylori antibodies, and the patient has never been treated for H. pylori, it’s pretty reasonable—especially in young patients—to prescribe a course of treatment for H. pylori and see whether the stomach symptoms get better,” Dr. Vashi says.

Older patients with symptoms should talk to their doctor about getting an endoscopy, because of the increased risk of stomach cancer, such as gastric adenocarcinoma, which is more prevalent in older populations. Those who’ve been treated for H. pylori should also be tested afterward to assess for any remaining infection that would require further treatment.

“We don’t do a good job in documenting that we have eradicated the bacteria,” Dr. Vashi says. “The way to do that is with a stool antigen test, which is very sensitive, or with an H. pylori breath test. Ideally, you should be tested about four to six weeks after you’ve been treated.”

Patients who have been successfully treated for H. pylori may experience an increase in stomach acid production, previously suppressed by the bacteria, that may increase the risk of acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Acid reflux may damage the esophagus and upper stomach and should be treated to help prevent long-term damage. Chronic or untreated GERD may eventually increase the risk for esophageal cancer.

“H. pylori causes chronic inflammation of the stomach lining, which in turn affects the acid secretion of the stomach. When the stomach has a constant low level of acid, you don’t get so much acid reflux, heartburn and all those symptoms,” Dr. Vashi says. “Once you treat H. pylori and the stomach is healed up, now they’re back to their original acid secretion. Those patients, you’ll be surprised, but they may end up having more acid reflux symptoms after they’ve gotten rid of the infection. They’ll come back and say, ‘My stomach feels real good, but I’m getting more heartburn now.’”

Your first stop probably won’t be to an oncologist when you’re dealing with an ulcer, but it’s important if you have H. pylori to be on guard for continuing symptoms that may be a sign of cancer. Gastric cancers are often diagnosed once they’ve progressed to advanced stages and have poorer outcomes because they rarely show symptoms in the early stages, or the symptoms may seem like a less serious ailment.

“We always check for H. pylori when we suspect gastric cancer because of the co-relationship between those two,” Dr. Vashi says.

“Chronic H. pylori can definitely lead to problems down the road.”

If you’ve been diagnosed with a cancer of the digestive system and want to learn more about treatment options at CTCA, or if you’re interested in a second opinion on your cancer diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.