A melanoma diagnosis can be both scary and life changing. This highly aggressive form of skin cancer is the fifth-most common cancer in men and women in the United States. While more than 90 percent of melanomas are discovered early and removed by surgery, leading to positive results, this cancer may be lethal if it spreads (metastasizes) to other parts of the body like the liver or brain.

Since the emergence of immunotherapy drugs called checkpoint inhibitors, however, the prognoses for those with metastatic melanoma have improved considerably. Checkpoint inhibitors interfere with barriers that prevent the family of blood cells called T-cells from attacking cancers. The impact of checkpoint inhibitors on people with metastatic melanoma of the skin has also paved the way for their use in treatment of many other types of cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors were the first immunotherapy drugs approved for cancers based on genetic features rather than where they formed in the body.

“Most of the immunotherapy we use today started with testing on melanomas because older types of treatments like chemotherapy were not very successful,” says Samuel Ejadi, MD, Medical Oncologist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America® (CTCA), Phoenix. “Melanoma led the way for how we can get the immune system to attack cancers.”

These drugs have improved survival and produced positive outcomes for many melanoma patients, most famously, former President Jimmy Carter, who was diagnosed in 2015 with metastatic melanoma that had spread to his brain. Carter, now 97, was still able to keep a rigorous schedule and even continue building houses with no evidence of melanoma after doctors treated him with radiation therapy and the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda®).

President Carter’s good-news story is now very common. Since 2011, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first checkpoint inhibitor drug ipilimumab (Yervoy®), the death rate for patients with melanoma has dropped from 2.7 per 100,000 Americans to 2 per 100,000. Experts predict deaths from melanoma will continue to fall in the decades to come. It’s interesting to note that melanoma deaths are dropping even as the number of new cases has risen sharply, according to the National Cancer Institute.

In this article, we’ll explore the causes and risk factors for melanoma and treatments that have improved prognoses for many patients.

Topics include:

- What is melanoma?

- Why is melanoma difficult to treat?

- Immunotherapy for melanoma

- Targeted therapy for melanoma

- Managing the side effects of melanoma treatments

If you’ve been diagnosed with melanoma and are interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.

What is melanoma?

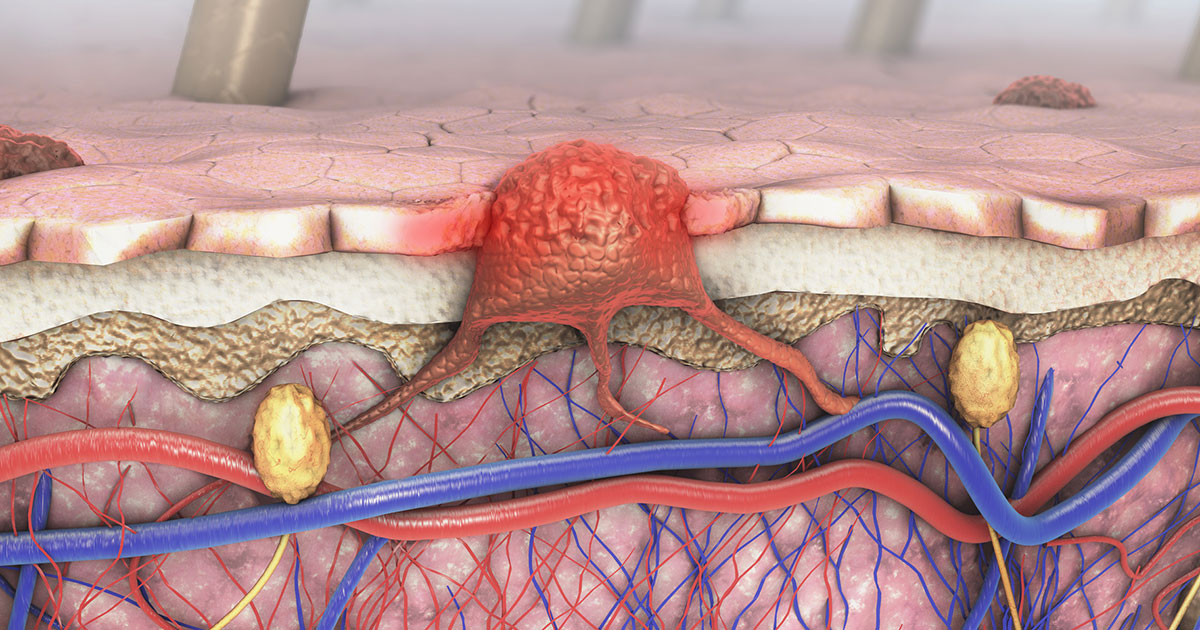

When you step out into the sunlight, the melanocytes in your skin are called into action. These skin cells produce and release a substance called melanin, the body’s natural pigment that gives color to your hair and eyes, and also determines the shade of your skin. Melanin protects the skin by absorbing cell-damaging ultraviolet (UV) rays from the sun and releasing more and more pigment, which often results in a deep, dark tan.

But when overexposed to UV light, melanocytes, like other skin cells, may become damaged, sometimes mutating and resulting in skin cancer.

The type of skin cancer someone develops depends on the skin cell type that has been damaged. For instance:

Basal cell carcinomas account for nearly 80 percent of all skin cancers. These slow-growing cancers rarely metastasize and are usually treated with outpatient surgery.

Squamous cell carcinomas account for about 20 percent of all skin cancers. These are usually caused by sun damage and are more aggressive than basal cell carcinomas, but usually do not metastasize. In people with compromised immune systems, however, they may be difficult to treat and may even be lethal. These are also treated with surgery but may require other treatments such as radiation, immunotherapy and sometimes chemotherapy.

Merkel cell carcinomas are a very rare form of aggressive skin cancer caused by a virus and sun damage. It requires aggressive treatment, including surgery, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and sometimes chemotherapy.

Melanomas are cancers that form when melanocytes mutate and begin to spread. While it accounts for about 1 percent of all skin cancers, melanoma is also responsible for most skin cancer deaths.

Learn more about the different types of skin cells.

What makes melanoma difficult to treat?

Unlike basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, melanomas are much more likely to spread. Many melanomas when caught early can be removed with surgery. However, surgery for melanoma is often more aggressive than those typically used for other skin cancers. Surgeons remove melanomas with larger margins—removing a wider area around the melanoma due to its ability to spread rapidly. The five-year survival for patients whose melanoma was detected early is more than 90 percent, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. When the cancer spreads, however, the survival rate falls to about 27 percent.

Melanoma is difficult to treat when it has spread because:

- It often spreads quickly and aggressively, and may be found in multiple locations in the body. Melanoma metastases are most often found in the lungs, brain, liver, bones, other parts of skin and lymph nodes.

- Multiple mutations may be driving the cancer’s growth, making it difficult to target a specific genetic feature for treatment.

- It has a way of shutting down nearby immune cells. Melanoma tumors are often surrounded by dormant or exhausted T-cells.

Ironically, some of these characteristics that make melanoma difficult to treat led to the development of new treatments like immunotherapy that are now used to treat many different types of cancers.

New treatments

In the past 10 years, new drug treatments have emerged that have dramatically altered the trajectory of melanoma deaths in the United States. Checkpoint inhibitors have been a game-changer for oncologists and their melanoma patients. Doctors also are turning to some new targeted therapy drugs in treating melanoma.

One question researchers are beginning to ask more frequently is if one drug works well, would two work better? The answer is increasingly yes. Researchers are discovering that combinations of these drugs are producing even better outcomes than when one drug is used alone.

“Before we had immunotherapy, we had chemotherapy, and it was only successful in a small percentage of patients,” Dr. Ejadi says. “The success rate of the immunotherapy that we use to treat melanoma now is very high. We have seen additional success with multiple combinations.”

Immunotherapy for melanoma

Various types of immunotherapy have been used to treat melanoma for years. They include:

Cytokines: These cell-signaling proteins help launch and regulate an immune response. They’re produced naturally by the body, but they can be synthesized and injected in high doses to treat cancer. The most widely used cytokines—interleukin-2 and interferon—produced very few long-term responses in patients. About 6 percent of patients with metastatic melanoma of the skin treated with high dose interleukin-2 may have experienced positive outcomes, but both types of cytokines often produced difficult side effects.

Oncolytic virus therapy: The theory is, if you inject a modified virus directly into a tumor, it’ll generate an immune response that attacks cancer cells. Many have tried (see a Duke University’s 60 Minutes report on patients whose glioblastoma tumors were injected with a modified polio virus). But so far, talimogene laherparepvec (IMLYGIC®) is the only oncolytic virus therapy approved to treat cancer. Also known as T-Vec, the drug uses a modified herpes virus injected directly into a melanoma mole or lymph nodes with melanoma. It’s had some success at shrinking the injected melanomas.

Enter checkpoint inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitor drugs work by disengaging the virtual parking brake on immune cells, allowing them to attack cancer cells. While researchers continue to look for more types of immunotherapy targets, so far drugs have been approved only for these two checkpoints:

Programmed death cell protein 1 (PD-1) on T-cells and its ligand PD-L1: A ligand is a protein that generates cellular activity when it interacts with a corresponding protein on another cell. When PD-1 and PD-L1 interact, the cancer cell appears to the immune system as a harmless normal cell. Most checkpoint inhibitors are designed to interfere with the PD-1/PL-L1 interaction to prevent the cancer cell from deceiving the immune system.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4): This protein, found on T-cells, helps to regulate how long immune cells are active and keeps the immune system from running amok. Sometimes, CTLA-4 may prevent immune cells from attacking cancer cells. The first checkpoint inhibitor approved in 2011, ipilimumab, is the only currently approved drug that targets CTLA-4 and was originally approved specifically to treat metastatic melanoma.

“The cells of our immune system are our soldiers, but they have a built-in brake that turns on after a period of time that prevents them from going overboard and causing inflammation,” Dr. Ejadi says. “This checkpoint inhibitor blocks the built-in brake, so they fight longer.”

Researchers have found that melanoma is a highly immunogenic cancer, meaning it has properties that make it capable of being seen and attacked by the immune system. However, some melanoma tumors are surrounded by T-cells that are exhausted or have been rendered dormant. Checkpoint inhibitors revive those T-cells and summon them into action.

Checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-1/PD-L1 also have been approved to treat cancers with specific genetic features, including a high tumor mutation burden (TMB). This term is used to describe when a tumor has a high number of gene mutations, several of which may drive the tumor’s growth and may also be seen by T-cells as foreign. Melanomas that have been caused by sun damage often have a very high number of mutations.

“The cancers that are more damaged have a lot of mutations,” Dr. Ejadi says. “The higher your mutation burden, the more likely that you’ll have at least one mutation that your immune cells are going to recognize and attack.”

Doctors also have found that combining a PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor with ipilimumab, a CTLA-4 inhibitor, has resulted in much better outcomes for many patients. One drug helps the immune system better recognize the cancer, while the other helps it fight longer.

For instance, a study published in 2017 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology found that metastatic melanoma patients treated with nivolumab (Opdivo®) and ipilimumab had a 63 percent survival rate three years later—higher than most patients with nivolumab alone.

The range of outcomes may vary wildly among patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors. Research indicates that some patients respond exceptionally, with no evidence of disease, while others may not respond at all. Response rates have improved as researchers learn more about these therapies.

Targeted therapy for melanoma

Targeted therapy drugs work by seeking out and attacking specific features on cancer cells. The key is finding the correct target.

“Everybody’s cancer is different because the number and types of it has mutations can vary from person to person and even from one metastasis to another within the same person in different places,” Dr. Ejadi says.

Of the many mutations found in melanomas tumors, among the most common are mutations into the BRAF gene. BRAF is one of several signaling proteins that help regulate cell behavior.

“Damage or mutations to the instructions in DNA, due to sunburns or other reasons, often leads to errors in manufacturing of the BRAF protein, which then acts like a stuck gas pedal in melanoma cells in about 40 percent of people,” Dr. Ejadi says. “Using oral drugs that block BRAF with specific mutations together with another protein in the BRAF pathway called MEK, can lead to rapid death of melanoma cells.”

In the past 10 years, the FDA has approved targeted therapy drugs that attack melanoma cells with a specific BRAF mutations commonly found in tumors. In addition to use in metastatic melanomas, the FDA has approved combinations of targeted therapy drugs—first generation vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) plus cobimetinib (Cotellic®) and second generation dabrafenib (Tafinlar®) plus trametinib (Mekinist®)—as adjuvant therapies for patients whose melanoma tumors were removed with surgery. Studies show that using these combination targeted therapy drugs improved survival in many melanoma patients.

“If DNA testing reveals one of several BRAF mutations,” he says, “using a combination of medications that block BRAF and the protein MEK may start to shrink melanomas as quickly as one week and has also been very effective in preventing very advanced melanoma from returning after surgery.”

Managing the side effects of melanoma treatments

The aggressive treatments that may be used to attack melanoma may produce a wide variety of side effects, from chronic fatigue to inflammation of various organs. Combining immunotherapy drugs may produce better outcomes for many patients, but they may also experience more severe side effects, including an auto-immune reactions such as colitis.

“Combination immunotherapy to treat more aggressive cancers is much more likely to be effective in the long term compared to a single agent immunotherapy alone, but more than 80 percent of people may experience side effects.” Dr. Ejadi says. “Fortunately, more than half of people do not experience serious side effects with combination immunotherapy.”

In most cases, side effects are short-lived, but in one study up to 43 percent of melanoma patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors experienced long-term side effects that lasted at least 18 months into the research. Most of the side effects were mild and included a rash or skin irritation, joint pains, or thyroid issues. Other side effects of checkpoint inhibitors may include:

- Fatigue

- Intestinal inflammation, diarrhea, and nausea

- Liver inflammation

- Eye irritation

- Hormone imbalances

Common side effects of targeted therapies that block mutated BRAF and MEK may include fatigue, fever, low blood counts, skin irritation, thyroid issues and liver inflammation. Since the range and duration of side effects for melanoma treatment vary so widely, it’s important to have a care team that understands how to diagnose issues and develop a care plan that helps keep the patient strong while maintaining his or her quality of life.

At CTCA, our care teams don’t just treat cancer; we also offer evidence-informed supportive care services that help manage the symptoms of disease and the side effects of treatment. In some cases, side effects may require clinical treatments, such as steroid therapy. In other cases, patients may consult with a supportive care provider who can help address, and sometimes prevent, specific issues. Supportive care services recommended for melanoma patients may include:

Nutritional support: An oncology-trained dietitian can help patients develop eating plans designed to help them get enough nutrition while dealing with digestive issues.

Pain management: A physiatrist or other pain management physician may help provide relief from treatment-related headaches or pain resulting from surgery or tumors pressing on nerves or organs.

Oncology rehabilitation: Massage therapy or other rehabilitation support providers may be able to help patients deal with treatment-related fatigue.

CTCA also provides behavioral health and spiritual support to help patients navigate the emotional toll of their disease and treatment.

If you’ve been diagnosed with melanoma and are interested in a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan, call us or chat online with a member of our team.