A cancer diagnosis often brings a number of challenges that patients are forced to navigate. In addition to the appointments, treatments, medicines, tests and logistics involved, not to mention the rollercoaster of emotions, patients and family members have to learn a whole new vocabulary they may not have seen, heard or experienced before. Doctors may have unfamiliar titles. Treatment options may involve advanced technologies. Words and terms may sound similar, but have very different meanings.

To clear up some of the confusion, the Cancer Center 360 blog developed an occasional series called, “What's the difference?,” to familiarize patients with cancer terminology and help increase their cancer IQ. Below are summaries of the series installments from the past year.

Autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplants

When the first stem cell transplant was performed in 1957 by E. Donnall Thomas, MD, the results proved less than promising. All six of Dr. Thomas’ leukemia patients died within 100 days of their transplants. Thirty-three years later, Dr. Thomas won the Nobel Prize in medicine for his work on stem cell transplantation. Today, the procedure, refined after decades of research, is the standard of care for patients with various forms of anemia and hematologic malignancies, such as leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Learn the difference between the two main types of transplants: autologous and allogenic.

Oncology specialties

Once they are diagnosed with cancer, many patients and their caregivers turn to the internet to decipher the intimidating medical lexicon they must begin to navigate. In addition to trying to learn about the many tongue-twisting chemotherapy drugs and highly scientific treatment protocols, consulting with the specialists who treat cancer—called oncologists—may also play a critical role in the journey. But first, it’s important to understand what these specialists do.

Biosimilar and generic drugs

Biosimilar drugs are often confused with generic drugs. Both are marketed as cheaper versions of name-brand drugs. Both are available when drug companies’ exclusive patents on expensive new drugs expire. And both are designed to have the same clinical effect as their pricier counterparts. But biosimilar drugs and generic drugs are very different, mainly because while generic drugs are identical to the original in chemical composition, biosimilar drugs are “highly similar,” but close enough in duplication to accomplish the same therapeutic and clinical result.

Adjuvant and neoadjuvant therapies

Fighting cancer typically involves more than one treatment. Most of the time, the disease requires a multidisciplinary approach, or a combination of therapies. Treatment plans often involve a primary therapy—generally surgery or radiation therapy—in addition to an adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant therapy. But many patients don’t know what these latter terms mean, or what purpose the treatments serve. In a nutshell, these are therapies, like chemotherapy or hormone therapy, delivered before or after the primary treatment, to help increase the treatment’s chance of success and decrease the risk of recurrence.

Male breast cancer and female breast cancer

Despite outward appearances, breasts in men and women are built very much the same. Human breasts in both sexes have nipples, fatty tissue, breast cells and ducts. Men and women also share some of the same risk factors for breast cancer. Both genders may have inherited mutations in their BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that increase cancer risk. And both genders produce estrogen, a hormone that at certain levels may increase breast cancer risk. So why do so few men get breast cancer?

Imaging tests

In the winter of 1895, while experimenting with electric currents and cathode rays, German scientist Wilhelm Röntgen stumbled across a discovery that would change medicine forever. It was called the X-ray, and its ability to take images of inside the human body has developed into a critical tool to help diagnose broken bones, lung disease and many other conditions. When it comes to cancer, X-rays are among many imaging procedures used to help diagnose and stage the disease and determine the effectiveness of treatments. CT-scans, MRIs, PET scans and others may create a confusing alphabet soup of procedures for patients. Our experts explain the differences.

Radiology and radiation therapy

Radiology and radiation therapy are critical components to many cancer diagnoses and treatments, but because of their similar names, patients often get confused by what exactly each does for them. Even though the names of the two fields of medicine share the same root, they use dramatically different technologies and techniques, and have wholly different purposes. X-rays, CT scans and other diagnostic imaging procedures—all radiology techniques—are used to help locate, stage and diagnose cancers. Radiation therapy, meanwhile, is a treatment that uses high doses of targeted energy to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. While patients are typically more familiar with radiology procedures because they have encountered them at other times in their lives, some find radiation therapy both foreign and intimidating.

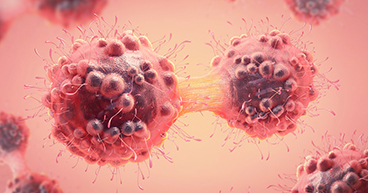

Benign and malignant tumors

There is no such thing as a good tumor. These masses of mutated and dysfunctional cells may cause pain and disfigurement, invade organs and, potentially, spread throughout the body. But not all tumors are malignant, or cancerous, and not all are aggressive. Benign tumors, while sometimes painful and potentially dangerous, do not pose the threat that malignant tumors do. "Malignant cells are more likely to metastasize [invade other organs]," says Fernando U. Garcia, MD, Pathologist at our hospital in Philadelphia. "They grow faster, and they are more likely to invade and destroy native organs."