The wisdom imparted by a caring extended family motivated Dr. Christopher Chen’s career choice and how he approaches patient care today.

Author Alex Haley described family as a “link to our past, a bridge to our future.” Pope John XXIII called family “the first essential cell of human society.” And Albert Einstein urged us to rejoice with our families “in the beautiful land of life."

Family means something different to everyone. While many families are less than perfect, for many, the idea of family represents security, love and an innate connection that cannot be broken.

For Christopher Chen, MD, family is all that and more. Family laid the foundation for his life’s accomplishments and, by extension, his career in medicine.

As a young boy growing up in Hong Kong and later in Vancouver, Canada, Dr. Chen lived with his parents, sister and his maternal grandparents and was often surrounded by other family members. The wisdom his grandparents imparted was not just in their daily advice or guidance, but also in how they managed their health issues. This proved pivotal in motivating him through school, in making his career choice and in how he treats his patients today as a Medical Oncologist and Hematologist at City of Hope Phoenix and the Outpatient Care Center in Gilbert.

As a young child, Dr. Chen remembers growing up in a “pretty traditional Hong Kong kind of setting where you have both parents working and the grandparents are the ones that really take care of the kids.”

His father was busy with his import/export electronics business and his mother worked full time for Korean Airlines. So, his mother’s parents moved from Korea to Hong Kong to care for young Dr. Chen and his sister. Living together in this inter-generational household, he remembers his grandparents as his primary caregivers.

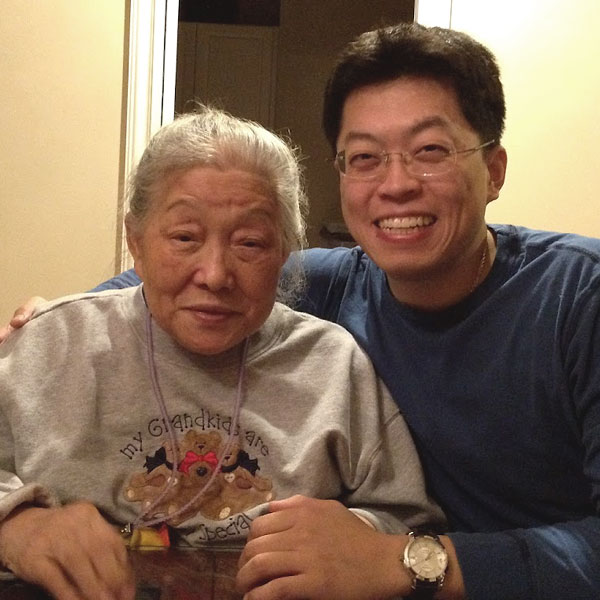

“I was very close to my maternal grandparents,” he says, which makes the time his grandmother had a fainting spell so memorable to him.

He was 6 or 7 years old, when his otherwise healthy grandmother went on an outing with relatives on a particularly hot, humid day in Hong Kong. Thirsty, she drank a lot of soda and passed out. Ultimately, she was diagnosed with diabetes, with the sugar from the sweet soda she drank that day likely causing the syncopal episode, Dr. Chen says.

“I just remember seeing my grandmother the day or two after and she was black and blue from having that episode,” he recalls. “I remember that very clearly, and so I told my grandmother that, ‘When I grow up, I'm going to be a doctor so I can help you, Grandma.’ ”

Dr. Chen’s family latched on to his desire to go into medicine and encouraged him to focus on academic achievement in the competitive Hong Kong school system — especially if he wanted to be a doctor.

“My parents would say, ‘You know, you can’t do medicine if you're not good in school.’ So, I mean that’s in my head, right?” he says. “So, in addition to having been brought up in that competitive atmosphere, I had this thing that I need to do well, especially in the science fields. And my parents did everything they could to help me out.”

But the pressures of doing well in school were about to get even more challenging.

When he was about 9 years old, his family was about to get larger, geographically speaking. His parents, sister and both sets of grandparents immigrated to Vancouver, Canada, where his parents’ siblings had already settled.

Dr. Chen did not speak English when he arrived in Canada, but the expectations to succeed in school remained.

“The language barrier was the most noticeable thing, but in all the math classes and science classes I was able to work around it, so I wasn't labeled a poor student,” he says. “I was just labeled the student who couldn't speak English. But I caught up.”

His dream to become a doctor and care for elderly people like his grandparents did not dim and throughout high school he rode his bike to a senior living community, where he worked as a volunteer.

“I just felt very comfortable around the elderly population just because I was brought up by my grandparents,” Dr. Chen says. “And so, I thought I was going to be a geriatrician when I do medicine.”

After graduating from high school in Vancouver, he went on to attend Washington University in St. Louis, spending time shadowing geriatricians from the medical school, set on following the path he set for himself as a child.

Around the time he started college, Dr. Chen’s maternal grandfather, who was there throughout his childhood, was diagnosed with lung cancer. He remembers flying home to Vancouver from college over Labor Day weekend to see his grandfather just days before he died.

His grandfather’s experience as a cancer patient proved pivotal to Dr. Chen’s later philosophy as an oncologist and physician.

“[He] was on treatment pretty much until the last week of his life and it was pretty miserable for him,” Dr. Chen says. “So, I always think about quality of life when I treat patients, because sometimes living longer doesn't necessarily mean living better.

“That has impacted how I practice because I always want to make sure that patients are very well-informed — and their families be informed — about the disease.”

Throughout his undergraduate years, Dr. Chen didn’t deviate from his goal of specializing in geriatrics. After graduation, he briefly worked in a research lab while “dabbling in finance,” since he also has an undergraduate degree in finance — and later earned an MBA. In 2005, he started medical school at the State University of New York, Buffalo, fulfilling the promise he made to his grandmother so many years before.

As he began his various specialty rotations as a medical student and resident, Dr. Chen remembers one of his professors and mentors advising him to keep an open mind about his ultimate choice of specialty.

“He said, ‘Keep your eyes open when you go to residency. Expose yourself to everything to see what you like,’ ” Dr. Chen recalls.

As he did a rotation in palliative care, where he encountered several cancer patients, he began to think seriously about alternatives to geriatrics.

“During that rotation and the hospice rotation, I saw a lot of cancer patients and even though their disease had unfortunately gone past the point of treatment, they were very close to or at least spoke very highly of their oncologists,” Dr. Chen says.

After doing several rotations in oncology, Dr. Chen found himself fascinated not only by the patient relationship aspects, but also with the science behind the disease. The science is so rapidly evolving it makes him “driven and excited about new treatment and drug approvals because it’s another tool I have in the bag to help patients out,” he says.

And based on his own experience with this grandfather and his father’s mother, who died of esophageal cancer when he was very young, Dr. Chen says he is sensitive to patients’ and their families’ needs.

“You can't just look at the disease itself and not worry about the whole patient, right?” he says. “In some ways, it's easy to give a certain chemo to a patient for a disease, but if I cannot manage their nausea appropriately, if they're having, little to no food or liquid intake, then I'm potentially hurting them more than helping them. So, managing side effects is absolutely vital to providing good care and treatment. That's how I practice — to make sure people are well informed about their disease, well-informed about their treatment options, well-informed about their side effects. Good or bad, I will always be honest with them.”

The influence of his family’s experience and the challenges Dr. Chen faced growing up, have given him a particular determination and competitive spirit — even when it comes to sports. He is an avid hockey fan — something he picked up when he moved to Canada and laced up his skates in an effort to fit in with his Canadian classmates.

“Everybody else had a couple years’ head start and I don’t think I was most gifted athletically, but I played other sports in high school,” Dr. Chen says. He adds that he was a pretty good skier, although since he has been in Arizona the last 13 years he hasn’t had much time to hit the slopes.

His competitive spirit also led him to his wife. Strangely enough, he met her after one of his friends challenged him to an eating contest and he began training in earnest to win the prize money.

“It [wasn’t] like real competitive eating, like the Nathan’s hot dog contest,” he says. “It’s just between a group of boys who are being not intelligent.”

Ultimately, the contest didn’t take place. But Dr. Chen joined a gym to help him burn off the weight he gained from all the extra calories he had eaten in training. It was in his cardio kickboxing class that he met his \wife, Julianne. The couple got engaged and married in 2013 and today don’t get to the gym too much to share workouts since they are caring for their 5-year-old daughter, Grace.

“Let’s just say, instead of getting [the contest prize money] that I got a wife,” he says. “It was worth it.”